> The beginning of the copper usage in the ancient world

> What are copper alloys?

> Manilla bracelets

> An ancient ship form Uluburun

> The bronze giant

> The Triumphal Quadriga of Lysippos

> The bronze Gniezno Doors

> Copper in the church

> Tee time by samovar

> Bells and bellfoundry

> Cannons

The beginning of the copper usage in the ancient world

Copper was the first metal used by man. Knowledge and skills related to its extraction and metallurgy has been developed for thousands years, the history of this process still hides many secrets.

The mineral deposits occurred in oxidation layer - in the first place malachite and azurite were known at the end of the Palaeolithic. Primarily, they were used as colouring, while green malachite was used to make for instance beads. Such findings are known from archaeological sites in Israel (Zagros, Shanidar), Iraq (Zagros, Shanidar), Iran (Ali Kosh) and many sites in Turkey (Anatolia). They can be dated to the period between 11th and 9th BC.

The beginning of the use of copper has its roots in Asia Minor in the area of so-called Fertile Crescent, covering today’s territory of Turkey, Egypt, Palestine, Iraq and Iran. Changes related to transition to sedentary lifestyle, development of economics based on agriculture and breeding, taking advantage of animals in transport and ploughing, horse domestication and creating craft specialization led to formation of governing centres, ruled by local elites.

Due to changes in social structures, there was a demand for luxurious goods, to which undoubtedly copper products can be included. Later beads, needles and other minor objects made from pure copper are known. They come mainly from the central and eastern Anatolia (Cayönü Tepe) and northern Iraq (the region of Zawi Chemi). About 6000 BC single copper monuments are known from Persia, Mesopotamia and Europe.

Metal, which was the most probably obtained from the local copper or copper carbonate rich in metal (malachite, azurite) was then hammer-hardened with a stone and wooden hammers, in single cases, mainly while producing copper foil – it could be firstly heated then forged.

First evidence of copper metallurgy - single slag – is known from the settlement Catal Hüyük and they are dated to 6500 BC. At the same site there were graves with copper objects, skeletons were covered by colouring obtained from malachite and azurite, and the textiles found in the graves were ornamented by thin copper wire.

At the turn of the 5th and 4th milennium BC there are first objects which can be perceived as bronze (copper alloys with arsenic and zinc). Arsenic bronze had silver colour, contrary to red copper and golden and brown zinc bronze. The latter alloy gained its popularity much later that is about 3500-3200 BC (findings from Ur in Iraq). The improvement in the process of metallurgy and considerably greater experience in copper metallurgy made at that time there were attempts to process sulphite ores, experiments with brass alloys were started (high content of zinc in metal). The specialists of that time had amazingly wide contacts with deposit exploring centres. Copper ores were imported from mines located several hundred kilometres away. Thus, in the area of metallurgical settlement from Nosuntepe, ores were processed coming from neighbouring deposits as well as those being 200 kilometres from this place (the Pontic outcrops, Ergani Maden mine).

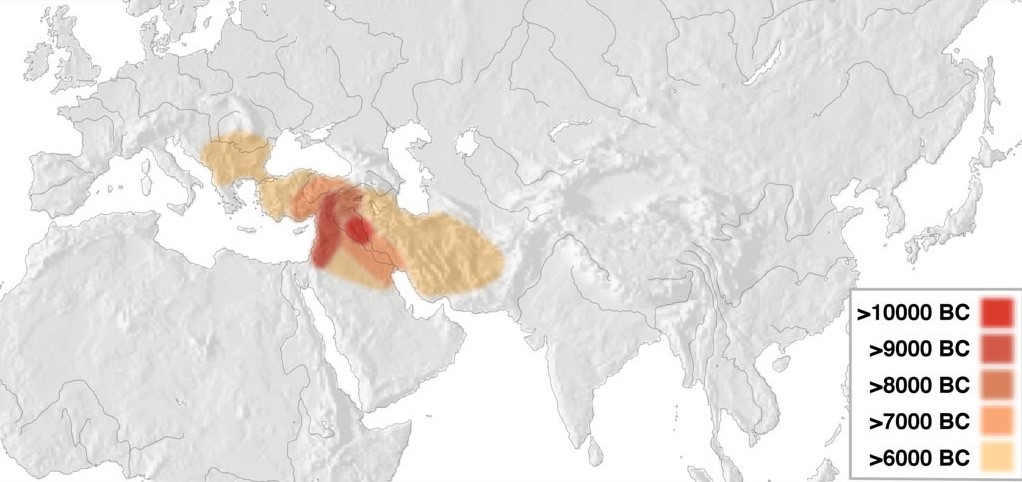

Knowlege of copper mining and metallurgy between 10 000-1000 BC, according to Roberts, Thornton and Pigott

Knowlege of copper mining and metallurgy between 10 000-1000 BC, according to Roberts, Thornton and Pigott

What are copper alloys?

They are alloys, in which copper is the very basic metal (except the alloys containing silver and gold, which are considered to be gold or silver alloys, if the content of these metals is equal to at least 10 %).

Bronze – alloy of copper and tin (Sn 6-22%) Brass – alloy of copper and zinc (Zn 20-50%) Tombac – alloy of copper and zinc (Zn >28 %) Gunmetal – alloy of copper with tin (Sn 4-11%), zinc (Zn 2-7%) and lead (Pb 2-6%) Alpaca (new silver) – alloy of copper with zinc, nickel, and manganese White copper – alloy of copper with nickel (Ni up to 10 %)

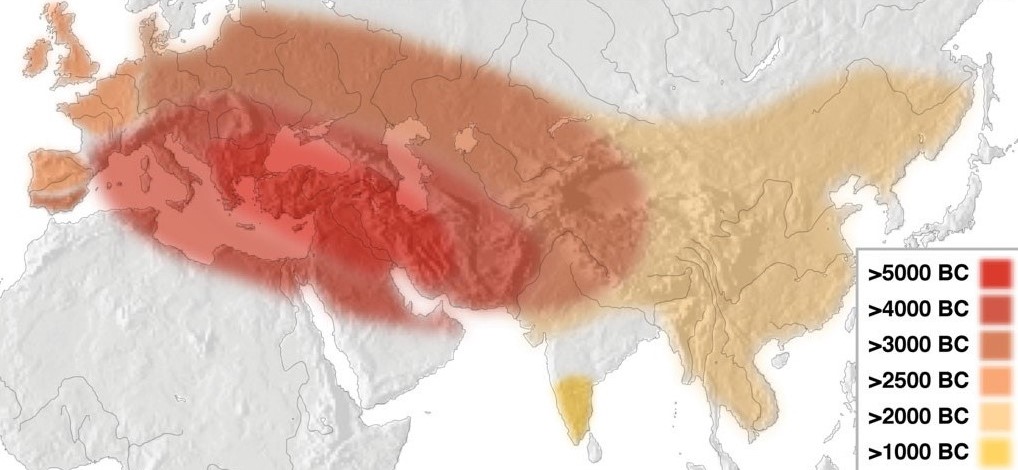

Copper alloys tree, according to ECI

Findings related to the bronze casting in the Bronze Age and the early Iron Age, collections of the Copper Museum in Legnica, photo by D. Berdys

Findings related to the bronze casting in the Bronze Age and the early Iron Age, collections of the Copper Museum in Legnica, photo by D. Berdys

Findings related to the bronze casting in the Bronze Age and the early Iron Age, collections of the Copper Museum in Legnica, photo by D. Berdys

Manilla bracelets

Manilla bracelets, mainly used to pay for a wife, being her private property. Worn by women on their hands, necks, and sometimes on ankles, they showed the financial wealth of the husband to the community. In case of a divorce, they were the protection of a woman and her children. They were used in Africa from the 15th century in the French, British and Portuguese colonies. They had various forms and sizes, also serving the slave trade. In Nigeria, the manilla was officially withdrawn in 1902, but their images appear on banknotes. In the Far East, the commodity money took the form of cast bars, knives, hoes or bells

Manilla bracelets, 18-19th century, collections of the Copper Museum in Legnica, photo by D. Berdys

Manilla bracelets, 18-19th century, collections of the Copper Museum in Legnica, photo by D. Berdys

Manilla bracelets, 18-19th century, collections of the Copper Museum in Legnica, photo by D. Berdys

An ancient ship form Uluburun

Where did the copper used during the Trojan conflict come from? The main source of this metal was Cyprus in antiquity. This raw material was the object of trade throughout the Mediterranean and shipped to civilization centres of that time, Egypt, Greece and Rome. The findings from 1982 in Uluburun, the proximity of Turkish island of Kos can prove the importance of copper trade from Cyprus in the late Bronze Age. The discovered wreck ship turned out to be a remaining of the ship from 14th BC, which were to sail from Cyprus or the eastern part of Mediterranean coast towards Egea, in today’s territory of Greece. The main part of the ship’s cargo were 354 rectangular ingots (cast ingots) of copper from Cyprus (in total about 10 tons), and additionally, one tone of tin. The latter is very likely to come from western regions of Mesopotamia or central Asia. Apart from them in the ship wreck there were a lot of valuable objects from Mediterranean including glass, ceramic dishes, Egyptian jewellery and amber.

Reconstruction of the Uluburun ship, according to C. Pulak

Possible route of the ship, according to C. Pulak

Copper bars extracted from the deck of a ship from Ulunburum, 14th century BC, according to C. Pulak

The bronze giant

The largest of the Hellenistic statues cast in bronze - the statue of Helios - stood on the island of Rhodes. He was on the list of the most extraordinary buildings of the ancient world, made in the second century BC by Antipater of Sidon, known as the Seven Wonders of the World. According to various estimates, the giant weighed from 30 to 70 tons. It was built by Chares of Lindos, a student of Lysa, in the years 292-280 BC. In order to commemorate the failure of Demetrios Poliorketes, who gave up the siege of the city in 305 BC. The inside of the colossus was filled with a skeleton composed of bars and iron rods. The individual parts of the casting were attached to them. The interior of the empty statue was filled with blocks of stone. The statue was about 30 meters high, stood on a 10-meter pedestal. The bronze giant was destroyed in 225/224 BC, as a result of an earthquake, but its fragments were on Rhodes for almost 1000 years. It was not until 653 that the remains of the colossus were taken away by the Arabs and sold in Palestine. The caravan transporting the work of Chares counted 390 camels.

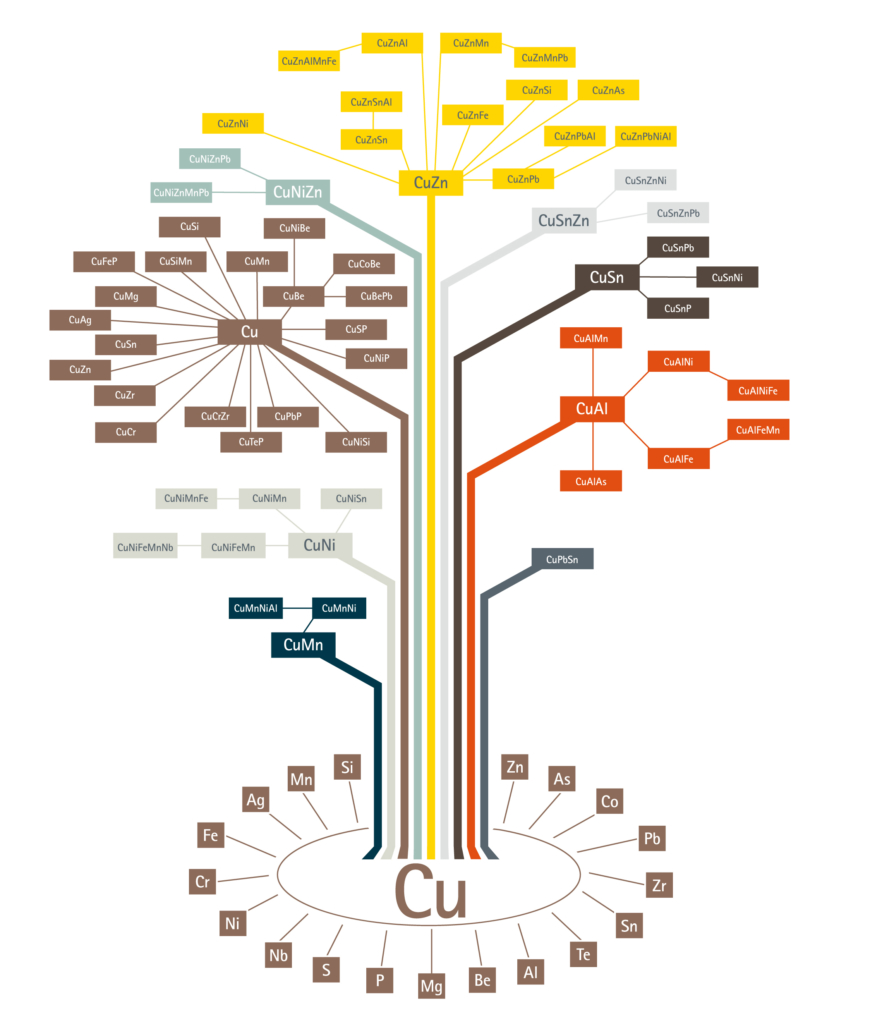

Colossus of Rhodes according to one of the reconstructions, public domain

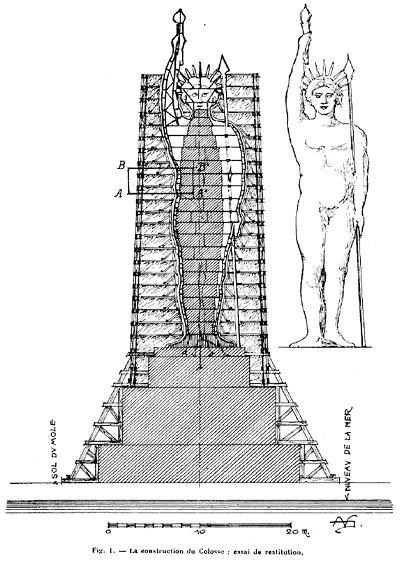

One of the possible ways to build a bronze statue of Colossus of Rhodes according to A. Gabriel

The Triumphal Quadriga of Lysippos

Pliny the Elder in Natural History (XXXIV, 63), describing the works of the famous sculptor Lysippos (4th century BC), mentions the statue of Helios on a wagon, commissioned by the Rodians. Unfortunately, the god of the sun alone has not survived, we know him only from other performances.

It can be assumed that the artist gave him a look similar to that of Alexander the Great. The steeds preserved to this day still arouse admiration, they are also the only monument of this type from antiquity. Not only proportions were given to the monument in a masterly way - which was a characteristic element of classical Greek art, but above all the movement and nature of animals.

The history of the quadriga is complicated, and its fate was intricate. During the reign of Emperor Theodosius (408-450 AD), the quadriga was brought from a small chute of Chios, a port in the Aegean Sea to the capital of the Byzantine Empire. Chargers decorated the imperial box at the hippodrome in Constantinople, to fall into the hands of the Venetians during the fourth crusade (1204). From that moment - with the exception of the short period when the quadriga was transported on the order of Napoleon to Paris and set on the Arc Carrousel - it is an ornament of the portico of the Basilica of Saint. Mark. You can now see copies of them.

Presentation of the Helios Quadriga from the Temple of Athena in Ilion (Troy), a public domain

.jpg?crc=4057086395)

Detail of Quadriga on the portico of the Basilica of Saint Mark in Venice

The bronze Gniezno Doors

The door was probably created at the turn of the third and fourth quarter of the 12th century, during the reign of Mieszko III the Old. They consist of eighteen rectangular fields, filled with multi-figure reliefs, illustrating the history of life and martyrdom of Saint Adalbert of Prague (in Polish: Saint Wojciech), patron of the Gniezno cathedral, and at the same time the first Polish saint.

The story of life of a later Bishop of Prague and a martyr opens the birth scene, located in the lower part of the left wing, and closes the relief of a solemn corpse placement in the tomb of the Gniezno cathedral. The individual scenes are surrounded by a border with a plant motif, complementing the scenes located in the main part. It is accompanied by motifs of symbolic meaning taken from the world of fairy-tale fauna and flora.

Buying the body of St. Adalbert of Prague by Bolesław I the Brave (in Polish Chrobry), one of the quarters of the Gniezno Doors, public domain

Copper in church

Church was an essential recipient of copper. Copper and its alloys were used to produce dishes (goblets, host cans, container for holy oils), dishes for ablution (washing hands before and during the liturgy), liturgical equipment (crosses, monstrance, reliquaries). The craftsmen’s products were gold plated and silver plated raising their aesthetic qualities, the inferiority of the material was hidden, protecting against oxidation. Gold plating of the interior of goblets resulted from the liturgical requirements and is used today as well. Copper and its alloys were also used to produce eternal lamps, incense boats, lit water vessels and baptisms, candlesticks and money boxes, bells and little bells.

Mass chalice, 17/18th century, collections of the Copper Museum in Legnica, photo by D. Berdys

Candlestick, 1730s, collections of the Copper Museum in Legnica, photo by D. Berdys

Lavabo vessel, 17th century, collections of the Copper Museum in Legnica, photo by D. Berdys

Holy water vessel, 18th century, collections of the Copper Museum in Legnica, photo by D. Berdys

Tee time by samovar

The homeland of samovar is Russia, although the English, Scandinavians and residents of the Middle East, especially Persia (today's Iran), were also eager to use this device. Tea was imported to Russia from Asia in the 17th century and was used initially as a medicine among the aristocracy.

The predecessor of the samovar was a copper vessel resembling a kettle with a large, curved spout and container for embers with holes at the bottom. The spread of samovars should be associated with the increase in the availability of copper, extracted on a large scale in the Urals at the beginning of the 18th century. Miners were often paid pure copper. They were so-called plate coins, flat bars of copper with a certain weight. From such coins, forged on the baking tray, various dishes were made and sold at fairs. According to sources, in 1778, the first "real samovar" was produced by the brothers Ivan and Nazar Lisicin. It happened on Sztykowa Street in Tula, in a small factory producing copper equipment, founded by their father - gunsmith Fiodor Lisitsyn.

Cylindrical samovar, after 1865, collections of the Copper Museum in Legnica, photo by D. Berdys

Flared samovar, late 19th century, collections of the Copper Museum in Legnica, photo by D. Berdys

Vessel samovar, 1860-1896, collections of the Copper Museum in Legnica, photo by D. Berdys

Bells and bellfoundry

Casting of bells, cannon barrels, statues and sculptures, as well as smaller items of bronze, brass and bronze (mortars, candlesticks, irons) were dealt with by the bellfounder. Metal used for the production of bells is an alloy with specific properties and composition. This composition is believed to have been developed in the Far East. Already during the Chou dynasty (1100-221 BC), tin-bronze bells with a content of approx. 15-20% tin were cast. Small bells had to be cast in bronze with a higher tin content, up to 33%. It was a harder bronze, therefore more brittle, but the composition of metals decided about its acoustic properties.

Bellfounder’s workshop according to the Behem Codex, the beginning of the 15th century

Bell made in 1718 by Christian Demminger from Legnica, collections of the Copper Museum in Legnica, photo by D. Berdys

Bells in the bell tower of the St. Peter and Paul Church in Legnica, photo by D. Berdys

Bells in the bell tower of the St. Peter and Paul Church in Legnica, photo by D. Berdys

Cannons

Bellfounders also made cannons and weapons. First usage of this type of weapon is confirmed in sources from Silesia in the 14th century. The composition of gunmetal was different than this one used for bells or other products. Bronze had to contain 8-15% of tin, a larger amount of this metal made bronze too brittle. At the end of the 16th century gunmetal was also used for casting barrels.

Cannons and mortars cast in bell-foundry were often a piece of art. Casting details are still awe-inspiring. The biggest cannon is the Tsar Cannon, cast in 1586, weighing 40 tons. The weight of the ball was 1 ton, it is hard to state if it ever shot.

Tsar Cannon in Moscow, 1586, public domain